When I moved to Scania, I noticed the birds. They were everywhere and of so many kinds. Most noticeable were all the birds of prey that seemed to hang over our heads all the time, like waiting vultures in a western movie, I didn’t know if it was just because of the open landscape and the very big sky, that I was unfamiliar with,-coming from Norway, as I were-, but my birdwatching friend Per told me that hundreds of millions of birds were passing over Scania every autumn and spring either going south or north from all of Scandinavia, Finland and even parts of northern Russia, choosing Scania, and particularly Falsterbo, as a pit stop, because of its close proximity to “mainland Europe” over at the Danish side of the strait. Choosing this stretch of open sea, not because the birds have problems flying long distances without rest, but because being over open waters make them vulnerable, therefore, the shorter time spent there, the better.

Since landscapes tend to change very slowly, I assume that this mass migration of birds have taken place here for thousands of years, probably all back to the ice age, and the thriving bird life of Scania must have been part of the everyday landscape scenery for people living here, always.

Noticing the birds in the sky, and around the pond in my garden was one thing, but it also seemed that whenever a Scanian archeologist thrusted his shovel in the ground he stumbled upon a bird shaped brooch of some kind, or a man-dressed-as-a-bird-shaped brooch, or something like that.

Uppåkra is an old place where cultic rites have been preformed for thousands of years. It is situated on the plain just south of what is now the town of Lund, and for sure the main reason why Lund was founded exactly there. Archeological finds tell us that there was a temple building of some sort, standing here for more than 700 years. And in the ground in this area there are lots of bird brooches found. The most spectacular piece of jewelry found here is the famous Völund brooch, a beautiful depiction of the master smith flying away from his captivity on the island, after he raped the king`s daughter and killed his sons, and made drinking bowls from their skulls. Völund is known from many old sagas from northern Europe. He has forged his mechanical wings, and the reason we can be certain it is depicting Völund, is because of the three drops of blood seen on one of his wings. After telling the king Nidhud what he had done, he fleed while the kings archers were shooting at him. But one of the archers is Völunds brother, and he aims at a little pouch that Völund keeps in his armpit, filled with blood, so it looks like he has been hit and wounded. The blood is from the king`s sons.

Brooches shaped as what seems to be birds of prey are found in this area by the dozens

The birds are seen from above, maybe as diving down hunting a prey, or just sitting, with their wings folded on their backs, its hard to tell, since we see the birds directly from above only, they have no side view aspect.

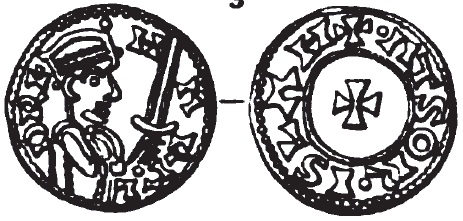

Dalby is a place just some 15 minutes away from Uppåkra, and one of the rivals to the position as the center of power in the Viking age, in competition with Uppåkra and Lund. Dalby was actually the earliest bishop`s seat in Scandinavia before Lund, and the church building there, is the oldest standing on the peninsula. The Danish king Harald Hein was buried in the church at Dalby in 1080, and his rival, brother, and successor to the Danish throne, Knut Sveinsson, moved the bishop`s seat to Lund, and thereby the center of power.

Coin with the portrait of the danish king Harald Hen….

A little bird, made of some cast copper alloy with delicate details and gilding, was discovered in this area as a stray find some time ago.

Although the bird appears a bit block-like and square with its modest shaping and modelling, it is well formed and executed with a keen sense of anatomy and details.

The bird`s talons form two flat brackets where a rivet has went through, and attached the bird to something flat vertically standing, The head of the rivet is still visible in one of the claws, the other claw is broken off at the rivets hole.

The figurine is more or less, symmetrical and is showing a bird with its wings folded on its back, and with its head down as if it is hunting. The wings are literally folded “on the Back” and form only a contour when seen from one of the sides, but when seen from above they shape a beautiful shield- like aspect with the feathers from the two wings intertwined in one another forming an interlaced pattern.

Seen from above it is surprisingly similar to the brooches found at Uppåkra, but then again, it’s a bird of prey seen from above, and that is a rather universal shape.

I have not done any thorough examination of the metal bird, only held it in my rubber-gloved hands for a couple of hours and taken some pictures,and made some measurements, but to me it seems like it is a cire perdu cast in some copper alloy with most of the finer details executed in the wax, but with some refreshing of the engravings done in the metal afterwards. It has then been gilded, and it looks a little bit like some traces of niello here and there, but the surface is fairly damaged and the artefact has not been cleaned, so its hard to tell for sure.

The damaged surface makes it hard to determine all the different features of the ornamental details, but since it is practically symmetrical, one can “guess” some details based on the details preserved on the reversed mirror-side, when that side is more intact. I am saying “practically symmetrical”, because when it comes to some of the engravings, they are made, based on the same idea, but executed differently on the two sides.

It also looks like the artisan has done some “sketching” directly unto the wax model, leaving traces of ornamental ideas that later were rejected.

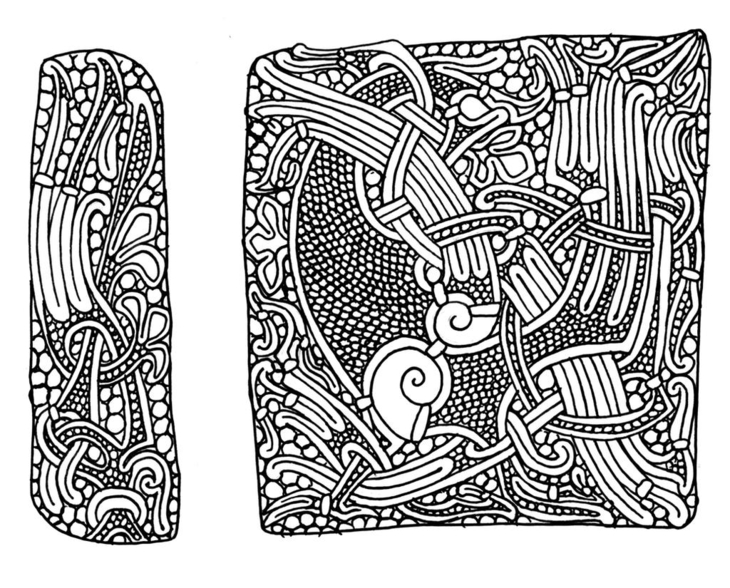

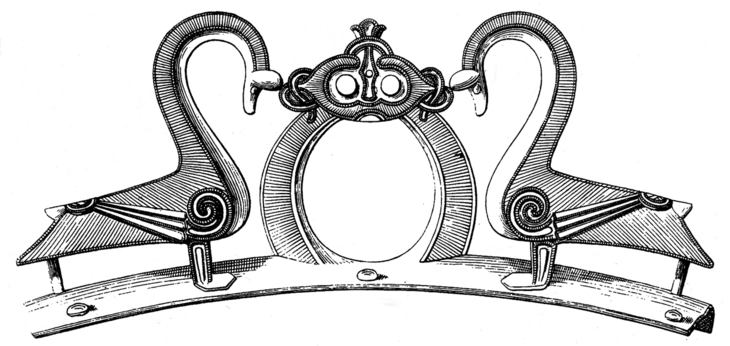

The reason I believe it is a cire perdu cast is, first and foremost because of the birds protruding eyebrow-loobs and the peculiar ribbon feature that ties together the two wings (see Illustration). These details are protruding and lying on top of the general shape and that goes for the entire wing-shield as well, and that means that these details have been put onto the “body”, either finished as loose pieces then attached, or, (as I believe for the eyebrow-loobs) put on and then shaped on the body piece. The engravings are well formed lines, (executed in the wax?) and they have afterwards been provided with small hatchings, making them shimmer and glow. A parallel to the hatched contour lines that can be seen on the Horse bows from Mammen for instance, only there the lines are protruding from the surface, and not engraved into the surface.

The amazing central mount on one of the danish harness bows. Here to illustrate the hatched outlines

Falconeering

Birds like this have been strong symbols and they have been used frequently in works of art, through Merovingian and Vendel time, and into the Viking age. The rich grave finds from Vendel and from Sutton Hoo are only some of the examples. From Sutton Hoo we can see this little enameled mount showing a big bird of prey attacking a small cute duck, which of course could mean a lot of different things, but to suggest it is depicting bird hunting, or falconering, is not far fetched. Falconering is a more than two and a half thousand years old tradition from Persia, and was introduced to Europe around 500 ad. The first written sources in Europe tell about falconering among Gallo Roman aristocrats

.

From all kinds of sources, written sagas and law books, grave goods from archeological finds and yes, also from art, we learn about falconering and how popular this sport was among the upper classes. Kings, queens and noble people got their falcons, hawks or even eagles with them in their graves, we read about falconering in the Volsungesaga, we learn that Randver picked the feathers of a hawk and sent it to king Jormunrek to tell him that he considered him old weak and helpless like the featherless bird, and in Sigurdskvadet, Brynhild wants two hawks to follow her in her funeral. Olav Trygvasson is, according to his saga, hunting a lot, and he also does some featherpicking on his sisters hawk, when she refuses to marry Erling Skjalgsson. And in “Skanelagen”, a 12th century law book from Scania, different punishments and fines are mentioned in relation to stealing another man`s hunting bird. Catching and training these hunting birds were of course extremely time consuming and to some extent expensive, but on the other hand, some scholars believe that in medieval time Europe, the site of a person in the streets with a bird on his shoulder or arm, would be just as common as seeing someone walking their dog, nowadays.

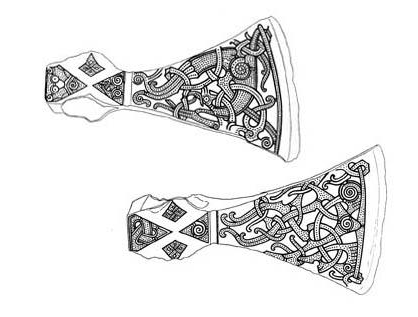

A bird with big oblong egg-shaped eyes pointing forward, and eyebrow loobs, possibly a beak/nose loob and a horse`s mane? This brings us right to the heart of the Viking age, stylistically. This is a creature You could find at, for instance the Cammin casket or on the Mammen axe, the wings are shaped like the ones we see at the antler box from Leon. But the way the feathers of the wings are arranged, and the symmetry, echoes the plant ornament from the Vang stone in Valdres, and the bird itself can be seen at the Alstad stone. Its cleanliness and well composed ornaments are definitely more Ringerike style, than the older Mammen style, but none of the bird`s features are so distinct that they can rule out any of the two styles.

Harness mount from lille Ihle, Denmark

Danish harness mount 10th century.

Bird from the Cammin casket late 10th century.

The central motif of the «Vang stone» from Valdres, Norway, shows interlaced tendrils in the same manner as the feathered wings of the little bird, as well as the same finials of the feathers.

The carved box from Leon, Spain, also show a very similar treatment of the wings.

The legs of the horse on the «Alstad stone», Norway are executed in the same manner as the legs of the bird. Double contour lines, interupted by the same «mounts» , and big spiral joints.

The bird on the «Alstad stone»

If we assume that this is an art object from this era, the 10th or 11th century, Scandinavian, it is interesting to look for similar objects that have been found. Cast copper alloy animals in the same style, same size and with the same features …(Heggen, Lolland, Källunge, Söderala Bamberg, Cammin Tingelstad. Grimsta, lille lihme og nordhaugen jelling etc)

Ringerike-style horse figurine from Lolland, Denmark. Beast from a weathervane. Same style, teckniques, size etc.

Lion from the «Heggen» weathervane, Norway. 11th century

«the Källunge lion» 11th century

Mount from one of the danish harness bows. 10th century.

Without jumping to conclusions, there are no doubt that the little bird has several features in common with the beasts adorning the weather vanes from this period of time. The size, the style, material, techniques, and even the way they all are being attached, or have been attached, to a vertically standing plate of some sort. But there are three things that make the bird stand out from the group.

- The bird has only one rivet for attachment to the plate, the other animals have two. Fixing a mount like this, that is supposed to endure a lot of impact from the elements, and from motion, with only one rivet, doesn’t seem like a very good idea, but at least the rivet is not round, nor is the rivets hole, they are both pentagonal, which will stabilize the figure a lot, and this is clearly not coincidental.

- While the other figures are fairly flat and have their side views as their main viewing angles, the bird has its most spectacular viewing angle from above, with its neatly decorated wings, although the sides, for sure, are decorative too.

- The bird is far more three dimensional than the other beasts, and displays more sophisticated metalwork.

The rivet is polygonal in cross section. It is not round.

The weathervanes, as they are called, are by many scholars considered to have been a lot more than just windexes. They were for sure mounted on the big warships, either in the top of the mast, or in the prow, as can be seen depicted on the rune-stick from Bryggen in Bergen. But they are considered also to have been the“merke” as mentioned continuously in the sagas and other written sources. “ Merke” is the banner of a warlord, that the soldiers gathered around during battles. From the 10th century there are some examples of miniature vanes found in the “Borre style”, but the big vanes still exciting, are all from the 11th century, and later on. These vanes are executed in the Ringerike-style and are named after the churches where they were found, used as weathervanes on top of the church towers spires. Söderala and Källunge from Sweden, and Heggen from Norway.

Stray find

Källunge, Gotland

Miniature vane, Borre-style.

The «Söderala vane» 11th century

“The ravens banner” is a flag with the same shape as the weathervanes, that is often mentioned in the sagas as a banner of war, used by Viking chieftains to strike fear into their enemies by envoking the power of Odin. The banner showed ravens of course. It can be seen at the Bayeux tapestry. Ravens are associated with Odin, war and Walkyries. Odin is the raven god with the ravens Hugin and Munin on his shoulders, war and battles are described in the sagas as “pleasing or feeding the ravens” and the Valkyries, the warrior goddesses that collected the fallen warriors from the battlefield and brought them to Valhalla, they were shapeshifters and often took the shape of ravens.

From the Bayeux tapastry. Under the horse is a banner lying on the ground….

English penny

Ravens banner. Also from the Bayeux tapestry

Coin with a raven.

Being a carver, the most obvious way to document a shape, – even though it is cast in metal, – is to carve a model out of wood. But a model like this will not tell anything about the techniques applied to the original, nor will it explain any of the qualities of the metal. But as a reference for me, in the further studies of the object, it is very handy. I don’t have access to the original, and therefore I must rely on photographs and the model.

Now I work with wax, to understand that process, and to do an, as good as possible, reconstruction, both of the process, and of the visual appearance of the object. Then, I wish to use the results of this work to recreate a suggestion of a bigger picture, and context, that this beautiful bird may have been a part of. I hope this can be interesting for other people as well.

I dont know if the artefact is a fake or not, and I dont know where this project leads me, but I will make updates here at the blog, as it goes along, and hope You will follow the journey…..