And the conference In the World of Balkan Range Architecture

English translation of this blog post

I had the privilege of representing the Norwegian Crafts Institute, together with Eivind Falk, at the tenth edition of the conference In the World of Balkan Range Architecture, hosted by the Etar Open-Air Museum in the heart of Bulgaria. This year’s conference gathered delegations from Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, and the two of us from Norway. The format combines theoretical presentations and lectures with practical workshops, excursions, and structured time for unstructured discussion and cultural exchange.

Unfortunately, I picked up a rather determined cold along the way, so my documentation from the event is a bit patchy. For the same reason my recollection of specific details might be imprecise, so any factual error in this text is entirely my own fault. The experience itself, however, was all the stronger—shaped both by seeing how many fascinatingly different ways there are to solve very similar technical details in our built environment, and, just as importantly, by discovering how much is virtually identical across language groups, national borders, and climate zones.

As an example of this, Eivind came across a particularly exciting Bulgarian example of what in Norway would be called a gvåvtak1 (or gvåv2-, kvav- or kavletak3, depending on the dialect area). This is a roofing technique of which only a handful of examples exist in Norway, and which—until that moment—neither of us knew about a single international example of. Yet here it appeared as a “perfectly obvious solution” (albeit a nearly extinct tradition) in this mountain region of Bulgaria. Might this become a topic for future collaboration and exchange?

“People need houses and houses need people.

—Ole H. Bremnes, from the poem/song Folk i husan

Etar Open-Air Museum was both the venue and the host of the event. Experiencing the site gave me a reason to completely reconsider what a “good” open-air museum can be. It is already a fairly common sentiment that “one of the worst things that can happen to an old house is to end up in a museum”—Balázs Szabó from Hungary presented several intriguing perspectives on this very problem. But the museum itself also served as a rich backdrop for further reflections on the issue.

As far as I understood while staying at the museum, there are hardly any old, relocated buildings at Etar4 in the most «materialistic» sense. There are a few notable historic structures that have always stood at the site, and has been carefully restored to its current state, and others that incorporate old—“authentic”—elements within otherwise “new”5 reconstructions. Large parts of the museum’s building stock however, I was told, have been rebuilt on-site from historical survey drawings. The originals were demolished in the 1930s but had fortunately been carefully documented. What visitors experience today are reconstructions containing not a splinter of original material, yet they nonetheless convey a striking picture of what once was6.

Set against examples like the Gol Stave Church at Norsk Folkemuseum—the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History—in Oslo, this raises some fascinating questions—is the stave church really “more authentic” simply because it contains more original material? The church at the museum has been given the form that was felt, in the 1880s, it ought to have had in the Middle Ages. Its exterior therefore consists almost entirely of 19th-century material7, and, “since the church was moved to the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History in 1907, a restrained interior decoration has been maintained, where the storytelling is focusing on the Middle Ages”8. It thus conveys neither the interior nor exterior appearance it had before its relocation, but rather conveys a story about how the Middle Ages has been imagined since the late 19th century and onwards.

I am sure there are elements of this at Etar too, but my impression of the museum felt somehow more convincing. I wonder if that credibility comes from the fact that, as reconstructions, the buildings are allowed to be shaped more fully by ongoing use? Potentially even more interesting than the buildings themselves was what the museum had filled them with—not just static displays, but as far as possible, living crafts in action. This is not unique in itself, but the proportion of “inhabited” buildings was far greater than I have experienced elsewhere, and I felt the habitation was allowed to organically color the buildings to a greater extent. This was perhaps especially noticeable in the village church on the grounds, which served both as a museum exhibit and simultaneously as an active place of prayer (to my understanding). The atmosphere this creates is something I have rarely (if ever) seen convincingly replicated except through genuine liturgical practice.

Of course, it’s also possible I was simply captivated by the sheer amount of running water and moving wheels and gears on the museum grounds—most of the buildings made use of water power in one way or another. Flowing water is, after all, hard not to get captivated by.

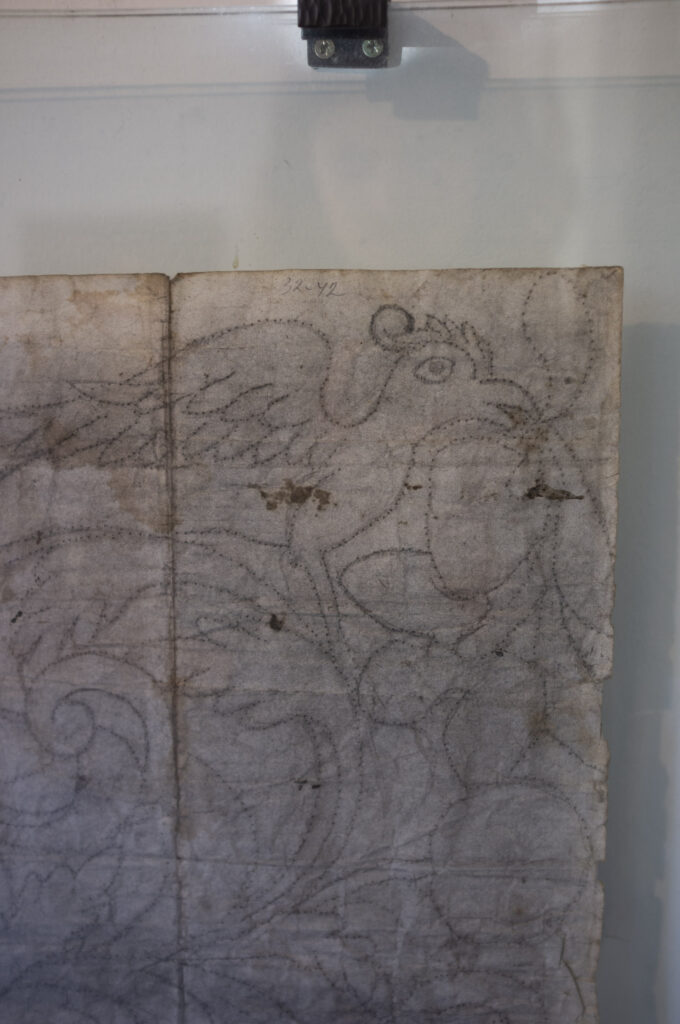

Equally fascinating was our visit beyond the museum to the living craft traditions of Tryavna. Here, we got a tour both of a museum of woodcarving; a school for art, woodcarving and design; and visited a few active woodcarving workshops. Experiences like this are all the richer with local hosts who open doors, translate, and share compelling stories and relevant context. Many thanks again to Eivind Falk and the Norwegian Craft institute for bringing me along on the trip, and to our wonderful hosts at Etar for the invitation. It was a wonderful experience and a great learning opportunity–I’m very much looking forward to the next opportunity to meet!

“People have boots, not roots,” as Eivind likes to say.

My blog posts, for their part, tend to have footnotes (sans boots):

- https://kulturminnefondet.no/prosjekt/gvavtak/ ↩︎

- https://lokalhistoriewiki.no/wiki/Leksikon:Takkonstruksjon ↩︎

- http://www.trefokus.no/resources/filer/fokus-pa-tre/42-Tradisjonsbaserte-byggemetoder.pdf and https://www.byggforsk.no/dokument/5156/ ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etar_Architectural-Ethnographic_Complex ↩︎

- The museum was founded in the early 1960s, so some of the reconstructed buildings have reached a significant age on their own. I wonder if some of these reconstructions now have existed longer as museum structures than their original counterparts did before they were demolished? ↩︎

- See Lars Roede’s excellent article on similar issues regarding the relocation of a 19th century city block from Meyerløkka in Oslo to the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History: “Flytting – forkastelig eller forsvarlig” (in Norwegian), in [Fortidsminneforeningens] Årbok 2004, 158th edition, pp. 35–46. Fortidsminneforeningen, Oslo, 2004. ↩︎

- From Folkemuseet: Stavkirke fra Gol. Available at: https://norskfolkemuseum.no/stavkirke ↩︎

- Own translation of quote from Folkemuseet: Dekor og innredning. Available at: https://norskfolkemuseum.no/dekor-og-innredning

Original text: «Etter at kirken ble overført til Norsk Folkemuseum i 1907, har man videreført en nøktern innredning der formidlingen fokuserer på middelalderen.» ↩︎

All photos by the author unless otherwise stated.

2 svar til “Travelogue from Etar, Bulgaria”

Thank you for sharing such a lovely account of your trip. Very enjoyable reading, and such excellent pictures! Etar Open-Air Museum has certainly made the (rather long) list of museums I would like to visit.

Thank you! It’s certainly worth the trip, both for the brilliant museum and the lovely people!