English version of «Har Hylestadportalen landets eldste spor etter geitefot-jern?» (9.11.2024), translated with the help of ChatGPT, manually checked and corrected by the author, posted to a separate blog post for clarity.

Report from a Study Visit to the Historical Museum in Oslo (Part I)

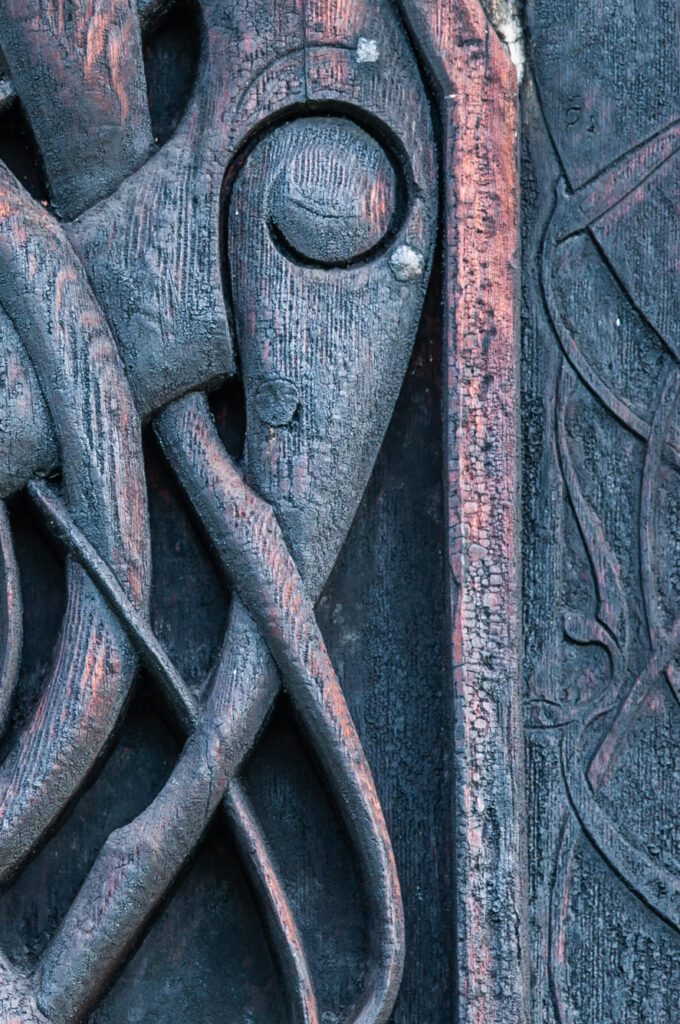

Embarrassingly, I hadn’t seen any of the current exhibitions at the Historical museum, so this somewhat dates my last visit. However, I felt I needed to see the medieval exhibition(s) there and also had an errand regarding the Hylestad Portal. A question arose recently when I was looking at close-up photos I took of the portal from the (demolished) Hylestad stave church while it was in storage a few years ago:

Are there traces of a parting tool (or «geisfuss»/V gouge) in the beard of Regin and the hair of Sigurd on the Hylestad Portal?

The parting chisel, often called «geisfuss» (borrowed from German), is a V-shaped carving chisel that can save time when carving lines of relatively uniform width. It’s not overly complex in principle and is relatively feasible to forge, but its use contains two distinct inherit challenges. Because it cuts both sides of the V-groove simultaneously, you will almost always be carving against the grain on one side. Thus, the parting tool must be exeptionally sharp, leading to the second challenge—it is significantly more difficult to hone and maintain sharpness compared to other chisels.

The shape of the parting tools, as other chisels, is usually hot-forged, then ground or honed to a keen edge. The forging process inevitably produces a scale on the steel surface, and some carbon also dissipates from the outermost layer of steel. The scale is iron oxide, which can’t be honed to a sharp edge. The carbon content in the steel is what makes it hard during tempering, so the surface that has lost carbon does not retain the same hardening capacity as the steel beneath. This means both the inside and outside of the carving chisel must be ground or honed after forging. For most chisels, this isn’t a major issue, but honing the inside of the goat-foot is an added challenge. It is essential for the innermost part of the V to be sharp and precisely shaped, yet it’s so narrow and difficult to access that it requires a honing stone of exactly the right shape and hardness. Good natural stones that grind well are often made of very soft rock, adding to the challenge. Making a functional V-parting chisel depends on crafting a suitable honing stone.

The other main challenge with the goat-foot gouge is honing it correctly. If you only sharpen the outside as if it was two angled knives, a pointy bit will remain where they meet. This happens because the inside can’t be formed into a perfectly sharp internal V, partly due to the previously mentioned honing issues. If this point isn’t honed away, it will tear up the wood in the bottom of the V-groove and render the gouge unsuitable for wood carving. If honed too far, the burr or “heel” of the goat-foot won’t cut well. Similarly, it won’t perform correctly if one side is honed more than the other. The honing angle must also be precise, as the gouge needs to be sharp to a degree far exceeding other chisels.

Given these challenges, it’s no wonder that V-parting chisels are nearly absent from woodcarving before the industrialization. They seem to have appeared in Germany in the 1500s (per Lara Dommeneghetti, private correspondence, Oct. 2024) but likely only became common with the technological advances during industrial revolution. In Norway, they probably emerged around the Baroque period, maybe in the 1700s or into the 1800s—essentially around the same time that industrialization made their production easier and more affordable. (If anyone has input on this timeline, I’d be happy to hear in the comments or otherwise!)

There’s nothing technically preventing the making of a V-parting tool in medieval Norway, but it simply wasn’t worth the effort in most cases. Whether the average blacksmith even considered forging such a tool, or the average carver contemplated asked for one, is another question.

V-shaped grooves on carvings from the Viking Age and medieval periods were typically made with knives1 in a series of two or three cuts. Sometimes, this is easy to spot, while other times, significant wear or precise craftsmanship makes it difficult to determine whether a knife or parting tool was used. But usually, knife tip traces can be found on medieval material, confirming that a parting tool wasn’t used. The prevailing opinion today is that the V-parting tool came much later and was unknown to medieval carvers. Erla Hohler (1999 Vol. 1, p. 62) supports this view.

Bo Granbo points out that craftsmen working on the Urnes Portal may have had unique tools (carving chisels) unknown to other carvers at the time. Therefore those tools were never made in significant numbers, and it’s unsurprising that these chisels are absent from the archaeological record.

“Knowledge of work at such depth, with specialized techniques and tools, may have been limited to a small group of craftsmen.” (Granbo 2024, p. 34)

Similarly, it’s possible that those who carved the Hylestad Portal had a variant of the V-parting tool in their toolkit, even if traces of it aren’t found in other portals or archaeological material. The Hylestad Portal, like the one from Urnes, stands out among stave church portals as an example of particularly high craftsmanship and artistry and may be the work of craftsmen unique to their time. The parting gouge (and its maintenance) could have been a trade secret that was not shared, possibly being the key to the remarkably intricate hair of Sigurd and Regin on the portal.

But my opinion alone doesn’t settle the question. What’s most interesting are the traces in the original material. The «Arv»/“Heritage” exhibition at the Historical Museum provides an excellent opportunity to see a good selection of stave church portals side by side. To establish a basis for comparison, I examined all comparable traces on the portals. I aimed to determine where there were distinct knife marks, thereby ruling out the parting tool in that instance, and noted the wear variations.

There are distinct knife traces in the V-shaped grooves on all other portals in the exhibition (Austad, Hemsedal, Sauland, Nesland, Ål, and Øye). The traces vary slightly, but they share common traits: the angle between the two sides of the V-groove varies, and one can always find remnants of sharp knife incisions at the bottom of the V. Variations in V-groove width are noted by (among others) Erla Hohler as evidence that a parting tool wasn’t used. It’s not definitive proof by itself since the groove width varies with cutting depth, but variation is more common when a knife rather than a parting tool is used. The most reliable evidence is finding knife tip incisions at the bottom of the V-groove. The parting tool is essentially shaped like two straight chisels at an angle, joined by a concave section in between, which is sometimes clearly visible. On the Hylestad Portal, the ornament surfaces have been hewvn down in recent times2, providing a very clear view of the bottom of the V-groove. The precise U-shape in the V-bottom makes it seem quite certain to me that a parting tool was used. (Fig. 9 arrow A)

This concave groove is the opposite of the sharp V-shaped bottom created by a knife. Isolated, a concave bottom could also result from weathering, which could mask knife traces. However, on the Hylestad Portal, the weathering is mild enough to see many other traces of the carving process, and the V-groove cross-section consistently shows the same concave bottom with no knife-tip marks. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, but in this case, the apparent complete lack of knife marks in the V-grooves on the Hylestad Portal is a strong indication.

The final point that convinces me that the Hylestad Portal has marks from a v-parting tool is the precision of these V-cuts in the beard of the smith Regin. (fig. 10) They are cut evenly, with no noticeable variation in width, across both the raised parts of the relief and the vertical planes, where it’s nearly impossible to reach with standard tools. These V-grooves are almost impossible to carve without specialized tools if done through a series of knife cuts. However, a thin parting tool could likely be used to reach as deep as shown in the image here.

One last aspect that makes the V-parting tool hypothesis for the Hylestad Portal even a bit more peculiar is that nearly all the rough forming on the portal was done with straight chisels—there’s hardly any evidence of curved chisels. If I were assembling a tool kit to carve a portal like Hylestad’s, I would prioritize some curved gouges much higher than a V-parting tool—they’re simpler to make, easier to sharpen, and more versatile. However, I doubt the mentioned details in the beard and hair could be carved as precisely as they are without a parting tool.

In the broader scope, the question of whether a parting tool was used isn’t the most critical for medieval research. But this example of using this gouge sheds interesting light on the unique nature of the Hylestad Portal, as well as illustrating a technological innovation that appears to have surfaced and vanished abruptly, only to re-emerge nearly half a millennium later.

Literature:

Granbo, Bo Alexander (2024) Urnesstilens håndverk: Nettverk av billedskjærere fra 1025 til 1150 [master thesis, University of Oslo] avaliable at: http://hdl.handle.net/10852/112820 ↩︎

Hohler, Erla (1999) Norwegian stave church sculpture volume I. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo. Page 62 ↩︎

I would love it if you leave a comment whether you found the English version helpful. Its a bit more work to make a dual-language version of these blog posts, but I hope it can lead to a broader discussion

- It is important to point out here again that «knife» is not synonymous with belt knife (tollekniv), see the blog post: En kjekk liten tollekniv og en påtrengende erkjennelse(norwegian). Try https://stipendiat-handverksinstituttet-no.translate.goog/treskjarerbloggen/en-kjekk-liten-tollekniv-og-en-patrengende-erkjennelse/ ↩︎

- ’Recent times’ in this context probably means after the stave church was demolished in the 17th century, around 1667 if one is to believe the former Riksantikvar Roar Hauglid. ↩︎

5 svar til “Does the Hylestad Portal Contain the Oldest Traces of a V-parting tool in Norway?”

I greatly appreciate the extra effort to publish the blog in English. Love your analysis, as always, but you have whetted my curiosity by mentioning Lara’s thoughts on the appearance of the v-tool around 1500. I wish there was more there, if only a link to research. Thank you for keeping this blog!

Thank you for commenting, feedback like yours make the work of writing this blog far more rewarding.

I’m curious myself about that suggested appearance of the v-tool around the 1500s, but haven’t managed to find other references to it yet myself. I have seen marks from v-tools in Norwegian carvings from the 1700s, and would expect Laras thought regarding when it was introduced in Europe to be fairly correct, but is still looking for further references. Will update both you and this blog if I find any.

And if you notice any other posts on this blog that is not yet translated, but that you think would be interesting to read in English, please don’t hesitate to reach out!

it is significantly more difficult to hone and maintain sharpness compared to other chisels?

That’s right – both because the shape of the chisel makes it (a little) more difficult to reach every part of the edge with a whetstone, and because the geometry of the edge must be just right for the v-parting chisel to work well. What makes it particularly challenging is that it can be perfectly sharp but still not work well if the geometry of the edge is not just right.

Interesting!