Report from the study trip to Oslo, Part II, with some notes from Maihaugen’s «Impulser» exhibition. A follow-up to «Does the Hylestad Portal hold the oldest trace of V-parting tool in Norway?». English translation of «Knivriss på kirkeportaler» (17.11.2024)

The second reason I wanted to visit the Historical Museum this time was to see if I could find traces of the layout-process. More specifically, I was looking for signs of how the ornaments were marked before the portals of stave churches were carved in the Middle Ages. I was especially interested in finding traces on any of the portals that might support the hypothesis that they were marked with a knife (as described by Kai here (in Norwegian))1. A closer investigation of this is, in my view, a necessary step in working on an alternative hypothesis that the markings might have been done with paint and a brush — that the ornament was calligraphed rather than drawn. This hypothesis was first proposed to the Urnes Project by Boni Wiik (English), but it closely aligns with the current prevailing hypothesis for how Roman stone carvers marked out letters to be chiselled into stone2. In that sense, it’s less radical than it might otherwise seem.

«It struck me at some point in life that you need real drawing skills to master the Urnes style, as opposed to the earlier Viking style forms which likely have their origin in the more or less three-dimensional objects they adorn. They hardly function graphically, unlike the Urnes style, which is purely two-dimensional line work. Thus, it became important for me to explore the origins of the various styles to understand them. Marius [Moe] constantly talked about the origins of serifs from brush strokes, and this led me quickly to extended Urnes-feet and snout curls.»

––Boni Wiik3

I would like to point out at the outset the important distinction between the process of drawing or marking the ornaments on the wood for carving and that of composing them. In a modern context, these are usually two separate operations – one composes the ornament on paper, in clay, digitally or in some other way, before transferring and marking it on the wood. If one goes back in time, it is far from obvious that these two steps are separate. Simple, decorated everyday objects, for example, were hardly drawn first on paper or the like. Similarly, there is much to suggest that the decoration on stave church portals was partly composed and constructed directly on the wood – Erla Hohler discusses this well4. One argument for this is how well the ornaments fit the height and width of the planks forming each side of the portals, despite the fact that these often are different sizes. Much suggests that the width of these is largely determined by the available wood, and the ornament adapted to the width they were given. The ornaments may have been planned in advance in general terms, but they were not necessarily composed ready-made.

It’s not self-evident that any of these marking or composing processes would leave any direct traces in the surviving material. Wood carving is a purely subtractive process, and all the surfaces where the markings were made will essentially be carved away. However, in the Urnes Project, we still found some direct and indirect traces that might remain from the marking process. For example, one of the spirals marking the hip or shoulder joints on the Urnes portal’s animal ornamentation was once marked, but it was carved out a few centimeters below the marking. The remaining lines were carved with a knife. However, it’s worth noting that these traces have a subtle V-shape, as if formed by multiple cuts rather than a single scratch — which might be significant for their interpretation. There are also some (very few) other places on the portal where one can see certain lines that might be knife scratches. More on them later.

At the same time, there’s something striking about the wear on the door leaf at Urnes Church, which may hold clues about the marking process. There is significantly more wear at the bottoms that were carved down than on the surface of the ornament that protrudes. Since the door is carved in a flat, extremely shallow relief, the surface of the ornament here is the same planed surface where the marking was done. Therefore, it’s tempting to wonder if the ornament was constructed by painting, with a medium that later protected the surface. Apart from this, there are notably few other signs of marking on the door leaf.

There are also some direct and other indirect signs of compasses being used. Erla Hohler points to an example from Iceland,5 Kai has noted some from Urnes, and this fragment from the Science Museum in Trondheim has a clear mark from a compass point exactly at the center of a notably circular loop.

That these marks have been preserved gives hope that we might find other traces of scratches elsewhere if scratching was used to «draw.» Alternatively, it also means that it could be significant if no scratch traces are found. Seeing the portals together in an exhibition also provides a valuable opportunity to view the whole, trying to form a picture from the similarities and contrasts between them. Therefore, it was very useful to spend a day wandering between them at the Cultural History Museum.

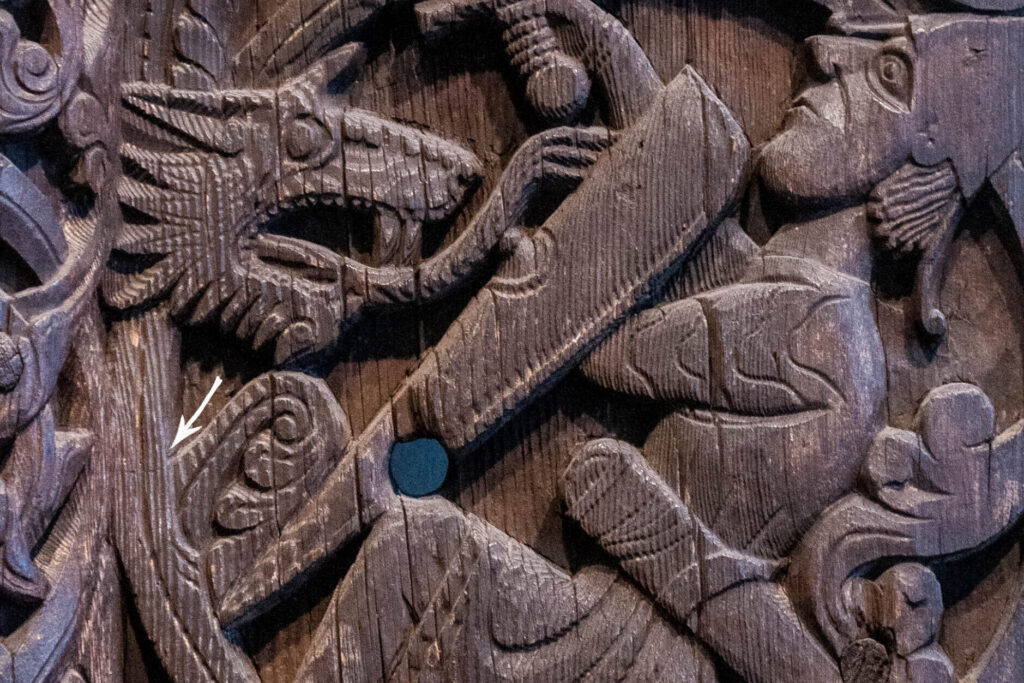

The most striking feature is how easy it is to find scratching marks on some of the portals. Even though it’s «plastic» ornamentation where much of the wood has been carved away, the outer parts of the ornament remain close to the original surface, showing clear traces of enthusiastic scratching with a knife or other sharp tools.

Below follows a review of the individual portals I studied. Interesting traces are marked with white arrows. Due to alarms and lighting conditions, it was challenging to take good photos that do justice to the traces. Where there were many traces of scratching, only a few are marked with arrows. See the descriptions of each one for further details.

Austad Portal has distinct traces of scratching with a sharp tool, where a line has been carved across nearly every element where it crosses over another.

On Hylestad, it’s almost impossible to find traces of scratching, which is especially interesting since the motifs are so similar. The only possible trace I found is a line just below the snakehead on the upper medallion, on the right cheek of the portal. But this could equally be an unfinished detail that was later changed during the carving process, rather than a trace of marking with the tip of a knife.

The Hemsedal Portal has visible traces of scratching with a knife. I also noted in the margin of my notebook, «not exceptional line work.» More on that later.

The Sauland Portal shows few traces of scratching; I may have found something that resembles it, see the image below. But this is the only one I found that could resemble a scratch.

The Ål Portal did not have visible traces of scratching. However, there were clear marks of a knife rather than goat-foot iron in the V-runes, which is interesting given the overall quality of the carving, especially when compared to Hylestad.

The portal parts from Øye also didn’t have visible traces.

Finally, there were generous marks from scratching on the Nesland stave church portal, though I didn’t spend much time on it.

Example of scratch marks on Nesland.

After a quick visit to «Impulser» at Maihaugen, I also found clear traces of knife scratching on both of the stave church portals on display there.

On the Bødal stave church portal, it was immediately hard to say whether there were signs of scratching. But it’s interesting to look at the weaving of the ornamentation on this portal, for example, about two-thirds up on the right plank. Here, there are traces that may indicate that the weaving wasn’t carefully planned, and one crossing seems to have just begun before the carver changed their mind and did it the opposite way. Could this indicate a marking method that didn’t give a good overview of the whole?

A little later, but still after a relatively short time, I did find clear marks from the initial scratching, despite significant weather wear.

The portal planks from Fåberg have clear signs of a marked outline that wasn’t followed — it looks like the carver marked up a sketch but then changed their plan. Still, these marks weren’t carved or planed away. There are also some signs of scratching elsewhere on the portal.

Moreover, it’s strikingly clear on this portal that compasses were probably not used to construct the circular elements in the ornamentation, and there is a striking absence of negative space in the ornament. There are also many traces of only one chisel-like tool, about one centimeter wide.

Although there are a few lines on both the Sauland and Hylestad portals that might resemble knife scratches, it should be emphasized that the amount of scratching on portals with visible traces was so extensive that they appear to form a distinct group. It therefore seems meaningful to talk about two groups of portals: those with clear scratching and those with little or no scratching. I have not found any truly convincing grey-area cases – including Bødal.

There are a couple of significant differences in the process and mindset between scratching with a knife and calligraphy with a brush. These are so distinct that they should also lead to differences in the results. This concerns marking visibility, ergonomics, and efficiency in the drawing process, negative space, contour versus midline, and overview in the carving process. It’s too extensive to go into all of these here, but I will try to address them individually later.

The first two factors where calligraphy might make a difference compared to knife scratching (but also drawing with a pencil) are visibility and ergonomics. When you calligraph the ornament, it immediately results in a «filled» drawing, whereas scratching with a pencil or knife only produces thin contour lines. On small objects, this may not be so important, but as the scale increases, it makes a difference. Contour lines make it difficult to step back and gain an overview of what you’re working on, and it’s easy to lose track of both the linework and composition. The thickness of the line doesn’t grow with the format you’re working on. Brushes and paint, however, are about building up the ornamentation as something that covers the surface rather than just contour lines, giving a good overview even from a great distance. We tested this successfully when Øystein Lønvik, August Horn, and I carved a freehand copy of the corner post from the Urnes style church last summer (2023).

Similarly, one gains a better overview during the marking process. Scratching with a knife requires a certain amount of force – some to cut and a lot to control the knife. Kai Johansen himself addresses some of the challenges this presents:

«Another issue that needs to be thought through is that if you use a whittling knife to mark V-shaped grooves, you almost have to pull the knife toward you to have good control. But then, can you manage to carve spirals or circular shapes? Will the knife leave nicks when it meets the wood grain?»6

––Kai Johansen

This forces one to work closely with the wood surface and limits the ability to maintain an overview of the linework. A brush, on the other hand, requires a light hand and large movements, and it can be used with an extended arm. This allows one to work from a much greater distance from the object, providing a broader perspective in the moment. The medium is also much more suited to transcend the inherent stiffness of the wood and compose the fundamentally plastic tendrils that we see in many of the medieval stave church portals.

The door panel of the Urnes portal is interesting in this context. As noted by Boni Wiik7, the ornamentation on the door is «almost like an exercise in drawing lines from knot to knot.» This makes the carving work significantly easier, since they mostly avoided carving through the knots, letting them remain in the finished, planned8 surface. At the same time, the linework remains apparently unaffected by this technique. This precise avoidance of the knots, combined with the effortless elegance of the linework, makes it clear to me that they used a technique for marking as well as composing that is both intuitive and allows for a good overview during the process. «Calligraphy» with a brush and paint is one such way of working.

It is relevant here to bring up the portals displayed at the Historical Museum. As I mentioned, I noted in the margin «not exceptional linework» about the stave church portal from Hemsedal. Similarly, Austad is not known for its finest linework, while Ål, Sauland, and Hylestad all appear to be of a different quality in composition. Nesland also has some traces of scratching and is probably not one of the most elegant portals. One should be cautious about setting up binary categories and clear divisions, but this may resemble a pattern that fits well with two distinct methods of working. One group where the ornamentation is «calligraphed» with a brush, often supported by compass markings and other geometric aids, as described by Erla Hohler9, and another group where the ornamentation is primarily composed through scratching with a knife. The latter is what Kai Johansen describes here and what can also be seen in many «graffiti» traces inside stave churches and other locations. I will return to an interesting case of such a dichotomy from Borgund Stave Church in a future post.

I promised to return to Urnes at the end of this post. To nuance the traces one should expect from each of the processes, it’s relevant to bring up again the experiments Øystein, August, and I did outside Urnes Stave Church last summer. We were to make a «freehand copy» of the carved corner post, which was not intended to stand as a finished replica, but rather to demonstrate techniques and processes for the audience, and test tools and methods for ourselves and the project. This meant we were free to take much greater risks in the work than we could on the actual portal copy, and with that, we could get much closer to what we perceived as the original process.

The material we used was a pine tree felled the same summer. Therefore, it had significantly higher moisture content than the original material likely had when it was carved. That material, in turn, was from a thicker tree, where only the heartwood remained, and it was probably felled in winter. Winter felling results in lower moisture content in the wood, and heartwood naturally has much less moisture than sapwood. The wood we used was considerably thinner than the original they used in 107010, and we kept the sapwood intact. This means the material we used had properties that differed significantly from the original. But the deviations in the material properties also forced us to focus more closely on reconstructing the process. Because the material was a bit too small in diameter, even with the sapwood intact, we had to adapt the ornament more than if the material had been «correct.» We used some guidelines to transfer the ornament geometrically in its roughest forms, but mostly we worked freehand, ensuring the ornament looked right. We started sketching with bits of charcoal, then gradually built up the ornament with a brush and black linseed oil paint. Linseed oil as a medium wasn’t ideal either from a historical authenticity perspective or from a practical standpoint in the work. Particularly the drying time, and how much transferred to our hands, clothes, and tools, was impractical, but other properties also made it less suitable. However, the way we built up the ornament as flat and filled lines made it possible to work both with the linework and negative space, close-up and from a distance. The method enabled us to transfer a complex ornament onto a challenging surface.

What makes this experiment especially relevant is how we ended up using a knife11 in the work. Once the ornament was built up with the brush and the surfaces and lines were set, shallow cuts in the surface were used to trim back to a sharp contour and define the weaving – a useful «tool.» In hindsight12, new rounds of testing have shown that this need would have been less with another type of paint, but some adjustments like this will likely occur anyway. These adjustments can also leave shallow «knife scratches» that could be interpreted as marks from direct marking with a knife. What differentiates the marks from these two approaches to marking is the braids in the ornament. To compose an ornament from scratch with knife scratches, it would be natural to scratch both elements of an ornament that cross each other, and then choose one of them to carve. Traces of this can be seen, for example, on the Austad portal. On the other hand, if the ornament is «calligraphed,» one would only need to carve the contour of the element that crosses over. Thus, both approaches to marking can result in traces of knife scratches, but these traces should have distinctly different characteristics.

The door panel of the Urnes portal becomes relevant again here towards the end. The surface of the ornament on the door is the same, presumably untouched surface on which the markings were made. This could suggest that it wasn’t scratched with a knife during the marking process, as it would have left traces – traces that, for example, they didn’t bother to remove from the previously mentioned «hip curl». This is not necessarily obvious when looking at Urnes in isolation, but when comparing it to other portals with visible traces of markings through knife scratches, there is a striking absence of scratching lines on the door. If the marking process had been the same as what can be seen in many other portals, there should be significant knife marks on these untouched surfaces. Similarly, there should be similar traces of knife scratches on nearly all stave church portals if this was the method they were composed with.

This post was primarily meant to report on some observations from two museum visits. However, the tendencies that became visible made it inevitable to draw some broader lines. It seems that the carved stave church material can be divided into two distinct groups when it comes to the marking process. The absence of scratching marks in one group does not automatically reveal which technique was used, but it makes knife scratching less credible for these. Similarly, I don’t think we can automatically conclude that all those with clear scratching marks were primarily drawn with a knife. For this group, knife scratches are more credible as a hypothesis. Without concluding, it seems plausible to point out that there are some clear tendencies in the material that should be further explored. Among other things, the ridge bell turret at Borgund has some interesting features in the ornamentation that can help shed light on this, and other carved parts from Borgund have some intriguing traces that I will bring up in a future post.

- Although Kai was the one who promoted the hypothesis of knife carving in the Urnes project, this hypothesis has longer roots in research, and has been described by, among others, Erla Hohler (1999:97), Martin Blindheim and Erik Fridstrøm (1984:88).

Fridstrøm, Erik (1984) ‘The Viking Age Wood-Carvers – Their Tools and Techniques’ article in Festskrift til Thorleif Sjøvold på 70-årsdagen. Oslo, Universitetets oldsaksamling. Available from: https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2007071200018 ↩︎ - Edward Catich is often credited as the most important person for formulating this hypothesis about the origin of serifs in brushstrokes. Many thanks to my good supervisor, friend and colleague of many years Lara Domeneghetti for introducing me to this theory, and lending me Catich’s work ‘The Origin of the Serif: Brush writing and Roman letters‘ (1968) when I was visiting London sometime before the pandemic. ↩︎

- Private correspondence 8.11.2024. ↩︎

- Hoher, Erla Bergendahl (1999) Norwegian stave church sculpture volume II. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo. Page 97 ↩︎

- Hohler, Erla Bergendahl (1993) Norske stavkirkeportaler – II studier (Doctoral dissertation) Utd. E. B. Hohler. Oslo. Available at https://www.nb.no/items/URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2015042408149?page=297 ↩︎

↩︎ - From Johansen, Kai (2023) https://urnesstavkirke.no/blogg-treets-mester/tanker-om-verktoy [read 12.11.2024] ↩︎

- Private conversation during assembly of the portal copy at Ornes, September 2024. ↩︎

- Probably «planed» with a skavl/pjål – I do not mean to insinuate that they used a hand plane in the modern sense in 1070. ↩︎

- Hoher, Erla Bergendahl (1999) Norwegian stave church sculpture volume II. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo. Page 97 ↩︎

- 1070 is the assumed year of construction for «Urnesstilens kirke» – for which the Urnes portal was made. See Thun, Terje; Stornes, Jan Michael; Bartholin, Thomas Seip og Sarva, Helene Løvstrand: «5. Dendrokronologi gir kirkene nytt liv». i Bakken, Kristin (red.) Bevaring av stavkirkene – Håndverk og forskning, 91–116. Pax forlag AS, Oslo. s. 107 ↩︎

- Important to note that a ‘knife’ does not necessarily mean a belt knife ↩︎

- My supervisor Lara Domeneghetti and I tried out several different types of paint and brushes in early November (2024), and found several alternatives that are both more plausible from a historical perspective, and worked better in practice.

More on this in a later post. See this post (linked). ↩︎

Photos (where nothing else is stated): Jon Anders Fløistad