English translation of «Pensler & maling for å kalligrafere stavkirke-ornamentikk», prepared using ChatGPT, and manually checked and corrected by myself.

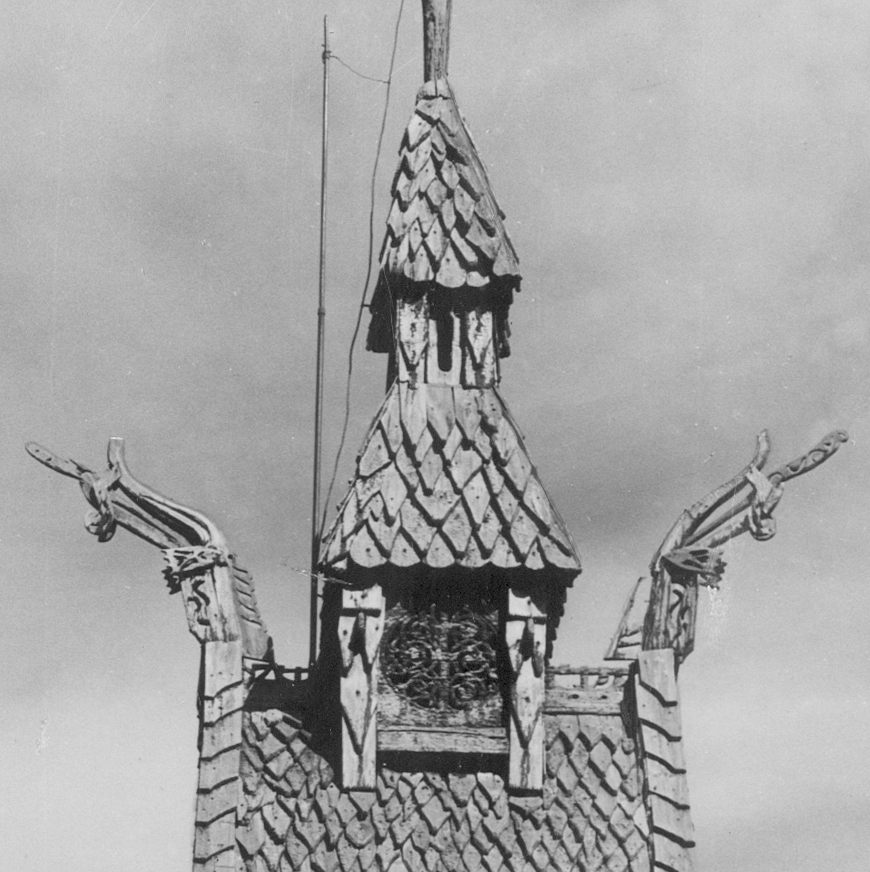

In October, my mentor and good colleague, Lara Domeneghetti, came to Oslo for a three-day ornament painting workshop. As I have described before, I am working from a hypothesis that some of the medieval stave church ornamentation is calligraphed rather than drawn, and few places seem more fitting for this hypothesis than in the second story of the Turret at Borgund Stave Church.

The hypothesis of ‘calligraphed ornamentation’ is not (entirely) new, but was proposed to the Fortidsminneforening’s Urnes Portal project by Boni Wiik. This project allowed for, and aimed at, digging into methods rather than just resulting in a finished artifact. But the ‘artifact’ must eventually be completed, and in this project, it should preferably resemble the Urnes Portal. So, certain simplifications were made, among them the use of relatively modern linseed oil paint and brushes for laying out the ornaments, and a decision was made to apply the marking relatively ‘mechanically’ with a direct transfer from the drawing. The subject was marked up with paint, but this paint was only an exercise in dragging the brush from dot to dot.

The entire premise of this hypothesis of calligraphed marking is that the marking technique influences the final result. Working towards a painted surface, rather than a pencil line, can, among other things, help with maintaining control in the carving, and the more spontaneous approach may contribute to a livelier result. Practical trials with brushes and paint so far have shown that both brush type, (painting) medium, and pigment again influence the flow of the marking, and therefore, it is natural to conclude that these seemingly small details, which do not directly concern wood carving, are also important in the larger picture.

Marking is also part of the whole process, and thus interesting in its own right. It is especially exciting because this way of working with a brush rather than a pencil, and with intuition and overarching structures rather than rigid plans, is far removed from what is conventional practice for woodcarvers today. It is also anecdotally intriguing that the technique is so close to the prevailing hypothesis of marking for Roman letters carved in stone.

Quod artificium, sicut visu et auditu didici, studio tuo indagare curaui1

From Theophilus: «This art, as I have learned from what I have seen and heard, I have endeavoured to unravel for your use.«2

The following text is a revised version of my notes from three intense days, so in line with medieval ‘handbooks’ on craftsmanship, it is a mixture of things I have been told, things I have misunderstood, and things I have experienced. To borrow words from Glenn Adamson: “As anyone who has tried to describe a skilled process knows, it is not possible to replace the actions of craft with a linguistic equivalent.”3

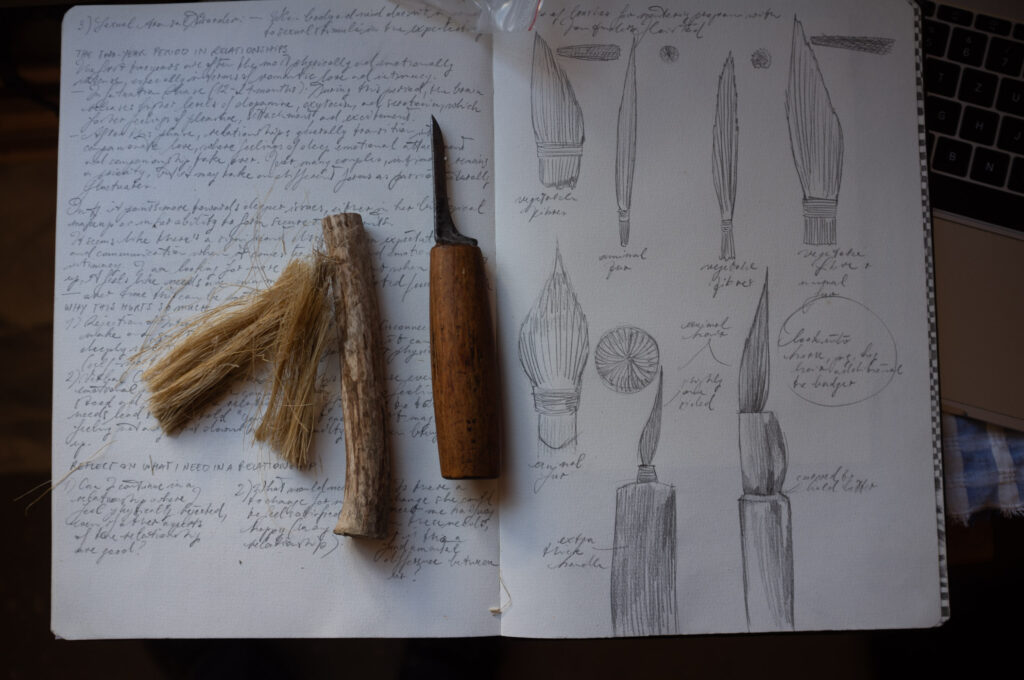

The First Exercise in Our Ornament Painting Workshop: Brush-Making

Very few brushes from the medieval period have been found in Scandinavia, so we had little archaeological material to build directly upon. Plant fiber bristles are the only types of brushes found in Scandinavia from the medieval period (as far as we have found out). According to Lara, they do not hold paint as well because the fibers are more disordered than in animal hair brushes, and they do not have the same springiness in the bristles – it’s a curious contrast to hold them side by side. However, with so little find material available, it cannot be ruled out that animal hair fibers were also widespread but have been lost. On the first day, we therefore made brushes with squirrel tail, flax fibers, and hemp fibers. We would have liked to try badger hair, but the badger skin we ordered did not arrive in time. We could have also tried hog bristles, which are the most common natural fibers in brushes today, but precisely because they are so widespread, it felt less exciting to try them. We also couldn’t get hold of suitable hairs in time.

We made the brush handles from twigs of elder wood, which have a relatively large pith, making them easy to hollow out. A hollowed brush handle where the hairs are glued in, possibly reinforced with wrapping, is advantageous because it results in bristles without voids, thus holding the paint better. Alternatively, the bristles can be supplemented with more hair outside the handle before being wrapped with thread. This results in a fuller and more sturdy brush without voids inside.

The wrappings that hold the bristles together and fasten them to the handle should be just tight enough, not too tight. If they are too tight, the hairs will spread in all directions. A technique where the bundle of fibers is first wrapped together at the middle, before one end is folded over the other so that all the fibers point in the same direction, proved to work well and has some historical precedents.

The bristles must be trimmed both in profile and on the sides – preferably to a long point to draw long lines. The thick part of the bristles holds paint, which is dispensed through the tip.

The starting point for making paint is a mixture of pigment and medium.

Many types of pigments could have been used. A good starting point for finding suitable candidates might be what is known from medieval decorative painting in the stave churches. Riksantikvaren, The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, lists the most common in medieval stave church art, including white lead, iron oxide red, and charcoal black.4 Cost is a reasonable selection criterion among these, since all the paint applied will ultimately be carved away. Finally, it is also an advantage if the pigment doesn’t have overly abrasive properties, as it would dull the tools when carving afterward. Earthen pigments are therefore less relevant for this reason, while white lead can be excluded based on cost.

We chose charcoal black because it provides a good contrast to the wood, has always been readily available and inexpensive, and is easy to work with. In some painting mediums (especially oil), charcoal becomes quite transparent, but this didn’t pose a big problem for us. Before charcoal can be used as pigment, it needs to be washed in clean water. If there are ash residues, they can create lye in the water, which will react unfavorably with the binder in the paint. To become a good pigment, the charcoal must be crushed into fine particles. We crushed the charcoal in a mortar until it became as fine a powder as possible, then ground it with a bit of water on a glass plate using a glass muller. Both the glass plate and the bottom of the glass muller have a slightly rough surface, and by moving the muller in circular motions through the wet pigment and water mixture, the pigment is ground into a smooth, fine grain size. The glass plate and muller are not historically entirely accurate, but a large flat stone for grinding and a smaller one in hand as a muller is a suitable alternative. This is also described as a common technique in more modern, yet pre-industrial rural painting in Norway.5

Binders or media for paint can be made from many different materials.

Linseed oil is popular, but it was not nearly as developed in the Middle Ages as it is today. That is likely the reason it wasn’t used in the interior paintings that have been preserved from the Middle Ages,6 and experiments in the «Treets Mester» project have also shown that it is not ideal for marking for wood carving. Especially evident when we compare attempts we made in the summer of 2023 outside the Urnes stave church with the trials we did this week.

Egg has also been a popular binder for paint, and many holy figures and icons have been painted with different variants of egg tempera. Tempera means that it is an emulsified paint – a mixture of two substances that normally don’t mix – and in egg tempera, it is an emulsion of oil and water, with egg as the emulsifier. Egg can also be used alone as a type of glue. We tried a variant of egg tempera in this experiment, more on that further down in the text.

Glue has a long history as a binder for paint – and in historical contexts, this often refers to protein-based glue. Glue paints can be made from milk protein (casein, «cheese glue»), fish glue, or hide glue, and based on my previous experiences, we decided to try glue-based paint this time.

Tar has long been used for wood surface treatment7. It is made by heating resin-rich heartwood from pine in the absence of air, so that the resinous substances and oils from the wood are distilled and can be collected. The content of resin and other substances makes it highly protective against wind, weather, and decay, but it has also been used for decoration – for example, on the masks under the ceiling of Høre stave church. It can also be pigmented to create a tar-based paint, and has also been used as glue. Tar is relatively expensive, must be applied hot, and often stays sticky for quite a long time. However, it may be that tar, prepared the right way, can become less sticky.

Based on frequent suggestions from various sources, the noticeable wear patterns at Urnes, and the fact that the only preserved brushes in Scandinavia are dipped in tar8, we also tried this. The tar we used is kiln-made pine tar and was given to the workshop for this purpose. We heated it in a water bath and thinned it with turpentine to make it spreadable, as it was quite viscous. It bled very quickly along the fibers in the wood. It improved slightly with the addition of charcoal pigment, but still bled too much to be a good line to work with. Furthermore, it stays sticky for a long time, and is expensive to use if it will only be carved away. It spread out nearly as well as egg tempera, but not as well as glue paint.

We also tried an egg tempera paint. It is made from egg, water, and pigment, and is applied cold. To prepare it, the egg white and yolk are separated. The opaque white residues/clumps are removed from the white, and the yolk is gently dried by moving it from hand to hand, while the hand not holding the yolk is dried with a towel. Finally, when the yolk is dry enough on the outside to stick to the skin, a small hole is made in the yolk. The contents are squeezed out and mixed with the egg white.

The mixture is then added to water measured with half an eggshell, and everything is shaken together. Finally, a little of the mixture is poured over the pigment, and everything is ground together into finished paint. This worked well, especially with the squirrel-tail brush. But it still wasn’t quite right for facilitating such a spontaneous process as the ornamentation of the Takrytter shows.

The winner of our experiments was glue paint. One part hare glue was mixed with ten parts water, and then charcoal was ground into it. The finished paint was then heated again in a water bath, and the result was a paint that spread very smoothly, was elastic in a way that «tightened» the brush, and gave nice, precise lines. The contours between painted and bare wood were significantly better than with linseed oil, egg, or tar-based paints. The elasticity and clarity fit well with a spontaneous and intuitive marking process, and a bonus is that the paint appears nearly «dry» as soon as it reaches room temperature. This allows carving to begin as soon as the brush is washed. This is in distinct contrast to oil, tar, and to some extent egg-based paints, which require days, potentially weeks, of drying before carving can start. Glue paint also worked surprisingly well with a brush with linseed bristles. This symmetry, between a well-functioning and well-documented medium, and a well-functioning brush with bristles made from the only preserved brush material from the period, is so striking that I’m a bit worried that it might really be this simple. But for now, it’s a good thread to follow further.

Thank you so much, Lara, for such a pleasant and productive few days! And thanks to Campus Gali for the linen fibers we used, and valuable insights!

Multa nota solito:

- Excerpts from Theophilus’ Latin, Prologue to book II, p. 37 in Dodwell, C. R. (1961) The Various Arts. Clarendon Press, Oxford. New edition in 1986. Available at: https://schedula.uni-koeln.de/index.shtml. Partially via Kroustallis, Stefanos (2014) Theophilus Matters: The Thorny Question of the Authorship of the ‘Schedula diversarum artium’ in Zwischen Kunsthandwerk und Kunst: Die ‘Schedula diversarum artium’, Volume 37 in Miscellanea Mediaevalia. de Gruyter, Berlin (p. 57). ↩︎

- Translation from Dodwell (1961) Prologue to book II, p. 37. ↩︎

- Glenn Adamson (2013) The Invention of Craft. Bloomsbury Publishing, London. ↩︎

- Bakken, Kristin (2017) Bevaring av stavkirkene. Pax, Oslo. p. 87 ↩︎

- Among others described on page 42 and beyond in Ellingsgard, Nils (1988) Norsk rosemåling. Oslo, Samlaget. Available at https://www.nb.no/items/407232fedc9b6758597e45f6a4d1427a?page=45 (only from Norwegian IP addresses) ↩︎

- Among others, see Bakken (2017) ↩︎

- See also Marumsrud, Hans (2022) NOTAT: TAKRYTTAREN PÅ BORGUND STAVKYRKJE. Chapter in Årbok 2022: Håndverk. Fortidsminneforeningen, Oslo. ↩︎

- This may emphasize the selection bias in the preserved brushes. Tar contributes a completely different durability than other types of paint, but is very difficult to wash out of a brush bristle. Brushes used for other types of paint may have been washed and used again and again, while a tar brush was unlikely to be cleaned – and when it was too stiff, worn out or no longer needed – thrown away. Cheap disposable brushes for tar thus have good prospects for preservation, while ‘proper’ paint brushes have little prospect of preservation if they fell out of use. ↩︎